If you read

my last post, you’ll know how I feel about an afterlife, life after death, or whatever you call it – there isn’t one. At least, I hope there isn’t one. I’m 99.99% sure there isn’t one. I’d be bloody surprised, and disappointed, if there is one. I don’t want one.

Many of those who’ll say they’re not religious still say they think there’s “something” after death. They’ll still talk about seeing Mum, Dad, or whoever has died recently, again. Ask them how and where, and they’ll be stumped for an answer. Not that I do. Ask them. That would be insensitive, I suppose, when they’re grieving. Still, I’d like to.

At a recent local

Forum of Faiths, all the other speakers had different versions of an afterlife to explain. Actually, I’m not sure they did explain, now I come to think about it. But they all expected an afterlife, where their God would be waiting for them. Would they spend eternity with people they liked, or would they have to share it with people they didn’t especially like? Would they be as they were when they died, even if they were old and wobbly? Or would they be restored to youth and vigour? Would they be recognisable at all, or survive as a patch of bright light, a spirit? None of them could tell me. They were all vague about the details.

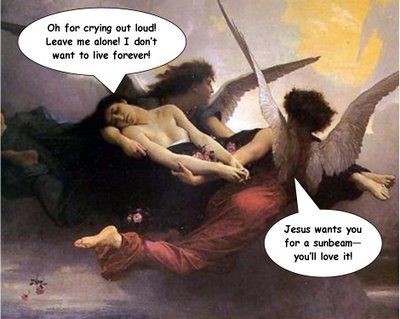

A few years ago, I took part in a local radio discussion about whether or not there’s an afterlife. The presenter wanted to talk about something that was more challenging than the usual local radio blandness, so she could refer to it in some sort of a presenter’s seminar she’d be going to. There were three of us; me, a Christian evangelist, and a woman who wrote books about psychic phenomena. The latter wasn’t in the studio with us. No, she didn’t just send psychic messages; she took part by phone. The evangelist was in the area because he was due to have a rally of some sort that evening, where he hoped to save a few sinners. The presenter revealed that the evangelist had lost his son in a road accident, fairly recently. It didn’t seem quite right to challenge him about whether or not he’d see his son again, under the circumstances, but he was keen to tell us that his son had felt there’s an afterlife too. The woman on the phone told everyone she’d got evidence of an afterlife, because so many people had told her about their experiences. As the discussion progressed, the evangelist got into his stride. I clearly annoyed him, especially when I said that I hoped there isn’t an afterlife, and asked what I’d be expected to do for eternity. God would have “responsibilities” for me, I was told. Surely, I said, there are many who’ll have had enough of responsibility at the end of their lives. Wouldn’t it be cruel to foist more on them? That made him crosser. How dare I question God’s wisdom and work plan? He didn’t actually say that, but it’s what he implied. At the end of the discussion, I think I won on points.

Some might imagine that when you die, your “soul” flies off, like Tinkerbell, and finds another host to inhabit. Wasn’t there a character like that in one of the TV sci-fi series a while ago? Was it one of the Star Trek offshoots? Deep Space Nine? No, hang on – it was a sort of parasite that outlived its hosts and then moved on, with all their collective memories intact. That was it. But I digress…

Some seem to imagine that people hang about, watching over their loved ones. My mum did. When I was young she used to tell me her mother, and God, were watching over me. I resisted the urge to say that there was no bloody privacy in our house anyway, without them spying on me too. That would have upset her.

In

The Life of Reason, the Spanish philosopher

George Santayana wrote:

It would be truly agreeable for any man to sit in well-watered gardens with Mohammed, clad in green silks, drinking delicious sherbets, and transfixed by the gazelle-like glance of some young girl, all innocence and fire. Amid such scenes a man might remain himself and might fulfil hopes that he had actually cherished on earth. He might also find his friends again, which in somewhat generous minds is perhaps the thought that chiefly sustains interest in a posthumous existence. But to recognize his friends a man must find them in their bodies, with their familiar habits, voices, and interests; for it is surely an insult to affection to say that he could find them in an eternal formula expressing their idiosyncrasy. When, however, it is clearly seen that another life, to supplement this one, must closely resemble it, does not the magic of immortality altogether vanish? Is such a reduplication of earthly society at all credible? And the prospect of awakening again among houses and trees, among children and dotards, among wars and rumours of wars, still fettered to one personality and one accidental past, still uncertain of the future, is not this prospect wearisome and deeply repulsive? Having passed through these things once and bequeathed them to posterity, is it not time for each soul to rest?

An afterlife – it’s all wishful thinking; a denial of death. Some hate the idea of not being here any more. Others hate the finality of separation from their loved one. I can understand that, but it doesn’t make immortality true. Let them imagine it, but don’t try to impose that view on me.

Immortality’s a horrible idea. In

Constructions,

Michael Frayn wrote:

Those who wish to abolish death (whether by physical or metaphysical means) – at what stage of life do they want the process to be halted? At the age of twenty? At thirty-five, in our prime? To be thirty-five for two years sounds attractive, certainly. But for three years? A little dull, surely. For five years – ridiculous. For ten – tragic.

The film is so absorbing that we want this bit to go on, and on…

You mean, you want the projector stopped, to watch a single motionless frame? No, no, no, but … Perhaps you’d like the whole sequence made up as an endless band, and projected indefinitely? Not that, either.

The sea and the stars and the wastes of the desert go on forever, and will not die. But the sea and the stars and the wastes of the desert are dead already.