It is necessary to the happiness of man that he be mentally faithful to himself. Infidelity does not consist in believing, or in disbelieving, it consists in professing to believe what one does not believe.

Thomas Paine, (1737-1809) The Age of Reason

Since I started conducting Humanist funerals in 1991, many more people have become aware that they have a choice about the form a funeral might take.

You can have your traditionally liturgical C of E service, which is often more about God and Jesus and less about the person who’s died.

You can have a non-conformist Christian service of various sorts, which may or may not include a relevant tribute to the deceased.

You can have a ceremony in accord with one of the minority faiths – I’ve never been to any of those, but have heard they vary in the amount of ritual they include.

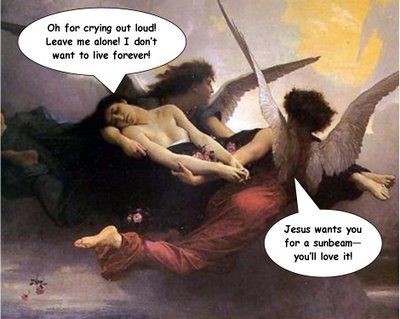

You can have a pick ‘n mix ceremony that’s not traditionally religious but includes religious elements, like couple of hymns and readings (usually sloppily sentimental) refering to an afterlife. People choose these for a variety of reasons. They might genuinely feel that a hybrid ceremony (as an atheist funeral director I know calls them) is appropriate, as they’re religious but not the organised sort. They might be confused but err on the side of caution – if there is a God, he, she or it might disapprove if he, she or it isn’t given a look in and send you to hell or wherever it is we non-believers are supposed to end up, according to some nasty believers. They might be worried about “what people might think” if they opt for a non-religious ceremony, because some still imagine that atheism is bad, religion is good. They might be too lazy or unimaginative to consider their options. They might be worried about upsetting conservative older relatives who are used to doing things the old-fashioned way, so they add familiar elements to appease them. They might not have any reason worth considering.

You can have a non-religious ceremony that’s conducted by a Humanist celebrant or one of those

Civil Ceremonies people, or anyone who provides such a service – it’s a free market.

What bothers me is the number of self-styled “humanist” celebrants (inside and outside

the BHA network) who are conducting pick ‘n mix ceremonies. They’re providing “what the families want” they’ll say. If that’s what the families want, fine – we know that such ceremonies are in increasing demand – but any self-respecting atheist won’t provide it. Humanists can be agnostics, they say, though I’m with the late

Douglas Adams and the still with us

Richard Dawkins in thinking that agnostic equals fence-sitting. However, there’s fence-sitting, and there's climbing over to mouth meaningless stuff rather than lose a client. Where’s their integrity?

Douglas Adams loved Bach's B minor mass, and so do I. There's lots of beautiful music that was written by religious people or for religious people and as long as we don't have to sing words that are either meaningless to me as an atheist, or that express things I profoundly disagree with (such as "All things bright and beautiful, the Lord God made them all") I don't have a problem with including it in a Humanist funeral. I'm OK with the bit in Ecclesiastes about "a time to be born and a time to die" - the bible's an anthology, not the word of God, and some of it's not religious - or with anything written by a religious author that's not actually religious.

There've been requests for inappropriate elements in Humanist funerals, such as a hymn. I've asked people whether they've listened to the words and the answer's often no, not really, or they've said, "But it's not really religious, is it?" about songs like

Amazing Grace. When I've read them the words, they've agreed that they're not appropriate for the funeral of a confirmed atheist. That's the trouble with religion; so few people have really thought about it, and how little sense it makes.

Ask yourself; would you rather have a celebrant who actually believed what he or she is saying and who stood for something (even if you don’t agree with him or her), or would you rather have someone who’d say

anything, however insincere? Suit yourself. I know what I’d prefer.

Humanists, the genuine variety, reject religion and are keen to demonstrate that it isn’t necessary for a satisfying rite of passage ceremony that reflects the personality and beliefs of someone who lived, and died, without it. Compromising our Humanist principles to provide a service for people who have

plenty of alternatives is a betrayal of all the sacrifices that have been made by those who've fought for the right to be free of religion. Not only that - the people who do it, don't get it - Humanism, that is.

I collect old photographs. This postcard was in a batch I've just bought from a dealer over the Internet. It appears to be a woman wearing mourning dress, though I've never seen this type of bonnet and veil before.

I collect old photographs. This postcard was in a batch I've just bought from a dealer over the Internet. It appears to be a woman wearing mourning dress, though I've never seen this type of bonnet and veil before.